Speaking Spanish in the Family United States Mixed Family

| United States Castilian | |

|---|---|

| Español estadounidense | |

| Native to | United States |

| Native speakers | 41.8 million (2019 American Community Survey)[1] |

| Language family | Indo-European

|

| Early forms | Former Latin

|

| Writing system | Latin (Spanish alphabet) |

| Official status | |

| Regulated by | N American Academy of the Spanish Language |

| Linguistic communication codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | es |

| ISO 639-ii | spa[2] |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | es-United states of america |

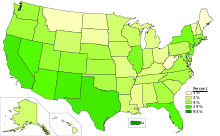

Percentage of the U.S. population aged v and over who speaks Spanish at home in 2019, by states. | |

The United States has over 41 million people aged five or older who speak Spanish at home,[one] making Castilian the second most spoken language in the Usa. Spanish is the most studied language other than English in the United States,[three] with about six million students.[four] With over xl million native speakers, heritage language speakers, and second-language speakers, the United States has the second largest Spanish-speaking population in the world after Mexico, surpassing Spain itself.[5] [6] About half of all United States Spanish speakers also assessed themselves equally speaking English "very well" in the 2000 US Census.[7] That increased to 57% in the 2013–2017 American Community Survey.[8] There is an University of the Castilian Language located in the United States too.[ix]

In the U.s. at that place are more speakers of Spanish than speakers of French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Hawaiian, the diverse varieties of Chinese, the Indo-Aryan languages, and the Native American languages combined. According to the 2019 American Customs Survey conducted by the US Census Bureau, Castilian is spoken at home past 41.eight million people aged five or older, more than twice equally many equally in 1990.[1]

Spanish has been spoken in what is at present the Us since the 15th century, with the arrival of Spanish colonization in North America. Colonizers settled in areas that would after get Florida, Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California as well as in what is now the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. The Spanish explorers explored areas of 42 of the future United states states leaving backside a varying range of Hispanic legacy in the Due north America. Western regions of the Louisiana Territory were likewise under Spanish dominion between 1763 and 1800, later the French and Indian State of war, which further extended Spanish influences throughout what is at present the Us.

After the incorporation of those areas into the United States in the first half of the 19th century, Spanish was after reinforced in the country by the acquisition of Puerto Rico in 1898. Waves of immigration from Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela, Republic of el salvador, and elsewhere in Latin America have strengthened the prominence of Spanish in the country. Today, Hispanics are ane of the fastest growing indigenous groups in the U.s., which has increases the employ and importance of Spanish in the United States. Still, there is a marked pass up in the utilize of Spanish among Hispanics in America, declining from 78% in 2006 to 73% in 2015, with the trend accelerating as Hispanics undergo language shift to English.[x]

History [edit]

Juan Ponce de León (Santervás de Campos, Valladolid, Espana). He was one of the get-go Europeans to arrive to the current United States considering he led the first European trek to Florida, which he named. Spanish was the first European language spoken in the territory that is at present the United states.

Early on Spanish settlements [edit]

The Castilian arrived in what would later get the United States in 1493, with the Spanish arrival to Puerto Rico. Ponce de León explored Florida in 1513. In 1565, the Spaniards founded St. Augustine, Florida. The Spanish after left but others moved in and it is the oldest continuously occupied European settlement in the continental Us. Juan Ponce de León founded San Juan, Puerto Rico, in 1508. Historically, the Castilian-speaking population increased because of territorial annexation of lands claimed before past the Castilian Empire and by wars with Mexico and by country purchases.[11] [12]

Spanish Louisiana [edit]

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, country claimed past Espana encompassed a big function of the gimmicky U.Due south. territory, including the French colony of Louisiana from 1769 to 1800. In order to farther institute and defend Louisiana, Spanish Governor Bernardo de Gálvez recruited Canary Islanders to emigrate to North America.[13] Betwixt Nov 1778 and July 1779, around 1600 Isleños arrived in New Orleans, and some other group of about 300 came in 1783. By 1780, the iv Isleño communities were already founded. When Louisiana was sold to the United States, its Spanish, Creole and Cajun inhabitants became U.S. citizens, and continued to speak Spanish or French. In 1813, George Ticknor started a program of Spanish Studies at Harvard Academy.[xiv] Spain likewise founded settlements along the Sabine River, to protect the border with French Louisiana. The towns of Nacogdoches, Texas and Los Adaes were founded equally part of this settlement, and the people there spoke a dialect descended from rural Mexican Spanish, which is now near completely extinct.[xv] Although it's commonly thought in Nacogdoches that the Hispanic residents of the Sabine River area are isleños ,[16] their Spanish dialect is derived from rural Mexican Spanish, and their ancestors came from Mexico and other parts of Texas.[17]

Annexation of Texas and the Mexican–American State of war [edit]

Spanish language heritage in Florida dates back to 1565, with the founding of Saint Augustine, Florida. Spanish was the first European linguistic communication spoken in Florida.

In 1821,[18] later on Mexico's War of Independence from Kingdom of spain, Texas was office of the United mexican states as the state of Coahuila y Tejas. A big influx of Americans shortly followed, originally with the approval of United mexican states's president. In 1836, the at present largely "American" Texans fought a war of independence from the central regime of Mexico. The arrivals from the US objected to Mexico'southward abolition of slavery. They declared independence and established the Republic of Texas. In 1846, the Republic dissolved when Texas entered the United States of America as a state. By 1850, fewer than sixteen,000 or 7.five% of Texans were of Mexican descent, Spanish-speaking people (both Mexicans and non-Spanish European settlers, including German Texans) were outnumbered six to 1 by English-speaking settlers (both Americans and other immigrant Europeans).[ citation needed ]

After the Mexican State of war of Independence from Spain, California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, western Colorado and southwestern Wyoming also became office of the Mexican territory of Alta California. Most of New Mexico, western Texas, southern Colorado, southwestern Kansas, and the Oklahoma panhandle were part of the territory of Santa Fe de Nuevo México. The geographical isolation and unique political history of this territory led to New Mexican Castilian differing notably from both Spanish spoken in other parts of the United States of America and Spanish spoken in the present-day United Mexican States.

Mexico lost near half of the northern territory gained from Spain in 1821 to the United states of america in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). This included parts of contemporary Texas, and Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming, California, Nevada, and Utah. Although the lost territory was sparsely populated, the thousands of Spanish-speaking Mexicans afterwards became U.S. citizens. The war-ending Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) does non explicitly address linguistic communication. Although Spanish initially continued to be used in schools and government, the English language-speaking American settlers who entered the Southwest established their language, culture, and police force as dominant, displacing Spanish in the public sphere.[19]

The California experience is illustrative. The showtime California constitutional convention in 1849 had eight Californio participants; the resulting country constitution was produced in English language and Castilian, and it contained a clause requiring all published laws and regulations to be published in both languages.[20] One of the starting time acts of the first California Legislature of 1850 was to authorize the date of a State Translator, who would be responsible for translating all state laws, decrees, documents, or orders into Spanish.[21] [22]

Such magnanimity did not last very long. As early on equally Feb 1850, California adopted the Anglo-American common police as the basis of the new country's legal organization.[23] In 1855, California declared that English would be the only medium of instruction in its schools.[14] These policies were one way of ensuring the social and political dominance of Anglos.[11]

The state'due south 2d ramble convention in 1872 had no Spanish-speaking participants; the convention's English-speaking participants felt that the state's remaining minority of Spanish-speakers should simply learn English; and the convention ultimately voted 46–39 to revise the earlier clause so that all official proceedings would henceforth be published only in English.[20]

Spanish–American War (1898) [edit]

In 1898, consequent to the Castilian–American War, the United states took control of Cuba and Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam every bit American territories. In 1902, Republic of cuba became independent from the United States, while Puerto Rico remained a U.S. territory. The American government required regime services to be bilingual in Spanish and English, and attempted to introduce English language-medium didactics to Puerto Rico, but the latter endeavour was unsuccessful.[24]

Once Puerto Rico was granted autonomy in 1948, even mainlander officials who came to Puerto Rico were forced to learn Spanish. Only xx% of Puerto Rico's residents empathize English, and although the island'southward authorities had a policy of official bilingualism, it was repealed in favor of a Spanish-but policy in 1991. This policy was reversed in 1993 when a pro-statehood political party ousted a pro-independence party from the republic government.[24]

Hispanics equally the largest minority in the United States [edit]

The relatively contempo merely big influx of Spanish-speakers to the United States has increased the overall total of Spanish-speakers in the country. They grade majorities and big minorities in many political districts, peculiarly in California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas (the American states bordering Mexico), and also in South Florida.

Mexicans first moved to the U.s. every bit refugees in the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution from 1910–1917, but many more emigrated afterward for economic reasons. The big majority of Mexicans are in the sometime Mexican-controlled areas in the Southwest. From 1942 to 1962, the Bracero program would provide for mass Mexican migration to the United States.[14]

At over five million, Puerto Ricans are easily the 2nd largest Hispanic group. Of all major Hispanic groups, Puerto Ricans are the least probable to be proficient in Spanish, but millions of Puerto Rican Americans living in the U.S. mainland are fluent in Spanish. Puerto Ricans are natural-born U.S. citizens, and many Puerto Ricans have migrated to New York City, Orlando, Philadelphia, and other areas of the Eastern Usa, increasing the Spanish-speaking populations and in some areas being the majority of the Hispanophone population, especially in Central Florida. In Hawaii, where Puerto Rican subcontract laborers and Mexican ranchers accept settled since the late 19th century, seven percentage of the islands' people are either Hispanic or Hispanophone or both.

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 created a community of Cuban exiles who opposed the Communist revolution, many of whom left for the United States. In 1963, the Ford Foundation established the first bilingual pedagogy program in the Usa for the children of Cuban exiles in Miami-Dade County, Florida. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 additional clearing from Latin American countries, and in 1968, Congress passed the Bilingual Educational activity Act.[fourteen] Virtually of these one meg Cuban Americans settled in southern and central Florida, while other Cubans live in the Northeastern United States; near are fluent in Castilian. In the city of Miami today Spanish is the first language generally due to Cuban immigration. Besides, the Nicaraguan Revolution and subsequent Contra State of war created a migration of Nicaraguans fleeing the Sandinista regime and civil state of war to the United States in the tardily 1980s.[25] Well-nigh of these Nicaraguans migrated to Florida and California.[26]

The exodus of Salvadorans was a result of both economic and political problems. The largest immigration wave occurred as a result of the Salvadoran Civil War in the 1980s, in which 20 to 30 per centum of El salvador's population emigrated. About 50 per centum, or up to 500,000 of those who escaped, headed to the Us, which was already abode to over 10,000 Salvadorans, making Salvadoran Americans the fourth-largest Hispanic and Latino American group, later on the Mexican-American majority, stateside Puerto Ricans, and Cubans.

Every bit ceremonious wars engulfed several Central American countries in the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans fled their state and came to the The states. Betwixt 1980 and 1990, the Salvadoran immigrant population in the U.s. increased nearly fivefold from 94,000 to 465,000. The number of Salvadoran immigrants in the The states continued to grow in the 1990s and 2000s as a result of family unit reunification and new arrivals fleeing a series of natural disasters that hit El Salvador, including earthquakes and hurricanes. Past 2008, at that place were well-nigh one.i one thousand thousand Salvadoran immigrants in the United States.

Until the 20th century, in that location was no clear tape of the number of Venezuelans who emigrated to the United States. Betwixt the 18th and early on 19th centuries, there were many European immigrants who went to Venezuela, only to later migrate to the United States along with their children and grandchildren who were born and/or grew up in Venezuela speaking Castilian. From 1910 to 1930, it is estimated that over 4,000 Due south Americans each year emigrated to the United States; however, in that location are few specific figures indicating these statistics. Many Venezuelans settled in the United States with hopes of receiving a better education, only to remain there following graduation. They are frequently joined past relatives. Yet, since the early 1980s, the reasons for Venezuelan emigration accept inverse to include hopes of earning a higher salary and due to the economic fluctuations in Venezuela which as well promoted an important migration of Venezuelan professionals to the US.[27] In the 2000s, dissident Venezuelans migrated to South Florida, especially the suburbs of Doral and Weston.[28] Other master states with Venezuelan American populations are, according to the 1990 census, New York, California, Texas (calculation to their existing Hispanic populations), New Jersey, Massachusetts and Maryland.[27]

Refugees from Spain as well migrated to the U.Southward. due to the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and political instability under the regime of Francisco Franco that lasted until 1975. The majority of Spaniards settled in Florida, Texas, California, New Jersey, New York City, Chicago, and Puerto Rico.

The publication of information by the United States Census Bureau in 2003 revealed that Hispanics were the largest minority in the Us and caused a flurry of press speculation in Spain about the position of Castilian in the United States.[ citation needed ] That year, the Instituto Cervantes, an organization created by the Spanish regime in 1991 to promote Castilian language around the globe, established a branch in New York.[29]

Historical demographics [edit]

| Twelvemonth | Number of native Spanish-speakers | Percentage of The states population |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 11 million | five% |

| 1990 | 17.3 million | 7% |

| 2000 | 28.one meg | ten% |

| 2010 | 37 million | thirteen% |

| 2015 | 41 meg | thirteen% |

| Sources:[xxx] [31] [32] [33] | ||

In full, at that place were 36,995,602 people aged five or older in the United states who spoke Spanish at dwelling house (12.eight% of the total U.S. population) according to the 2010 census.[34]

Current status [edit]

Public simple school sign in Spanish in Memphis, Tennessee (although in Castilian, DEC and January would be DIC and ENE respectively).

Although the United States has no de jure official language, English is the ascendant language of concern, education, government, religion, media, civilisation, and the public sphere. Virtually all state and federal regime agencies and large corporations use English as their internal working language, peculiarly at the management level. Some states, such as Arizona, California, Florida, New Mexico, and Texas provide bilingual legislated notices and official documents in Spanish and English and in other ordinarily-used languages. English is the home language of nigh Americans, including a growing proportion of Hispanics. Between 2000 and 2015, the proportion of Hispanics who spoke Castilian at home decreased from 78 to 73 percent.[35] As noted above, the only major exception is the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico in which Spanish is the official and the almost commonly-used language.

Throughout the history of the Southwest United States, the controversial event of language equally function of cultural rights and bilingual state government representation has caused sociocultural friction between Anglophones and Hispanophones. Spanish is now the most widely-taught second language in the U.s..[36]

California [edit]

California'due south first constitution recognized Spanish-linguistic communication rights:

All laws, decrees, regulations, and provisions emanating from any of the iii supreme powers of this Country, which from their nature crave publication, shall be published in English and Spanish.

By 1870, English-speakers were a majority in California; in 1879, the state promulgated a new constitution with a clause nether which all official proceedings were to be conducted exclusively in English, which remained in effect until 1966. In 1986, California voters added a new constitutional clause by referendum:

English is the official language of the State of California.

—California Constitution, Fine art. 3, Sec. six

Spanish remains widely spoken throughout the state, and many government forms, documents, and services are bilingual in English and Spanish. Although all official proceedings are to exist conducted in English:

A person unable to sympathize English language who is charged with a crime has a right to an interpreter throughout the proceedings.

—California Constitution, Art. 1. Sec. 14

Arizona [edit]

The state, like its neighbors in the Southwest, has had close linguistic and cultural ties with Mexico. The land, except for the 1853 Gadsden Purchase, was role of the New United mexican states Territory until 1863, when the western half was made into Arizona Territory. The surface area of the old Gadsden Purchase spoke mostly Castilian until the 1940s although the Tucson area had a higher ratio of anglophones (including Mexican Americans who were fluent in English). The continuous inflow of Mexican settlers increases the number of Castilian-speakers.

Florida [edit]

La Época is an upscale Miami section shop, whose Spanish proper noun comes from Cuba. La Época is an case of the many businesses started and endemic by Castilian-speakers in the United States.

First settled by the Spanish in the 16th century, 19% of Floridians now speak Spanish, which is the most widely taught second language. In Miami, 67% of residents spoke Spanish as their first language in 2000.

Most of the residents of the Miami metropolitan area speak Spanish at home, and the influence of Castilian can even be seen in many features of the local dialect of English language. Miami is considered the "capital letter of Latin US" for its many bilingual corporations, banks, and media outlets that cater to international business. In add-on, in that location are several other major cities in Florida with a sizable percentage of the population able to speak Spanish, most notably Tampa (18%) and Orlando (xvi.half-dozen%). Ybor City, a historical neighborhood shut to Downtown Tampa, was founded and is populated chiefly by Spanish and Cuban immigrants. Almost Latinos in Florida are of Cuban (particularly in Miami and Tampa) or Puerto Rican (Miami and Orlando) beginnings, followed by Mexican (Tampa and Fort Myers/Naples) and Colombian ancestry.[ commendation needed ]

New Mexico [edit]

New Mexico is commonly thought to take Spanish every bit an official linguistic communication aslope English language considering of its wide usage and legal promotion of Spanish in the state; however, the state has no official language. New United mexican states's laws are promulgated in both Castilian and English language. English is the state government's newspaper working linguistic communication, but government business is often conducted in Spanish, particularly at the local level.[ citation needed ] Castilian has been spoken in New United mexican states since the 16th century.[37]

Because of its relative isolation from other Spanish-speaking areas over most of its 400-twelvemonth existence, New United mexican states Spanish, peculiarly the Spanish of northern New United mexican states and Colorado has retained many elements of 16th- and 17th-century Spanish lost in other varieties and has developed its own vocabulary.[38] In addition, it contains many words from Nahuatl, the language that is notwithstanding spoken by the Nahua people in Mexico. New Mexican Castilian also contains loanwords from the Pueblo languages of the upper Rio Grande Valley, Mexican-Spanish words (mexicanismos), and borrowings from English language.[38] Grammatical changes include the loss of the 2d-person plural verb grade, changes in verb endings, particularly in the preterite, and the partial merger of the second and tertiary conjugations.[39]

Texas [edit]

In Texas, English is the state's de facto official linguistic communication although it lacks de jure status and is used in regime. However, the continual influx of Spanish-speaking immigrants has increased the import of Spanish in Texas. Although it is a part of the Southern United States, Texas'due south counties bordering Mexico are mostly Hispanic and then Castilian is commonly spoken in the region. The Texas government, in Section 2054.116 of the Government Lawmaking, mandates providing past country agencies of information on their websites in Spanish to assist residents who have express English proficiency.[forty]

Kansas [edit]

Spanish has been spoken in the land of Kansas since at least the early 1900s, primarily because of several waves of immigration from Mexico. That began with refugees fleeing the Mexican Revolution (c. 1910–1920).[41] There are now several towns in Kansas with significant Spanish-speaking populations: Liberal, Garden Urban center, and Contrivance City all have Latino populations over 40%.[42] [43] [44] Recently, linguists working with the Kansas Speaks Project have shown how high numbers of Spanish-speaking residents have influenced the dialect of English spoken in areas like Liberal and in other parts of southwest Kansas.[45] There are many Spanish-language radio stations throughout Kansas, similar KYYS in the Kansas City area as well every bit various Spanish-language newspapers and tv stations throughout the state.[46] Several towns in Kansas boast Spanish-English dual language immersion schools in which students are instructed in both languages for varying amounts of fourth dimension. Examples include Horace Isle of man Elementary in Wichita, named after the famous educational reformer, and Buffalo Jones Elementary in Garden Metropolis, named after Charles "Buffalo" Jones, a frontiersman, bison preservationist, and cofounder of Garden City.

Puerto Rico [edit]

The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico recognizes Spanish and English equally official languages, but Castilian is the dominant first language. This is largely due to the fact that the territory was under Castilian control for 400 years, and was inhabited by mainly Spanish-speaking settlers prior to being ceded to the United States in 1898.

Place names [edit]

Considering much of the US was in one case under Spanish, and later on Mexican sovereignty, many places have Spanish names dating to these times. These include the names of several states and major cities. Some of these names preserve older features of Castilian orthography, such as San Ysidro, which would be Isidro in modern Spanish. Later, many other names were created in the American period past non-Castilian speakers, often violating Castilian syntax. This includes names such every bit Sierra Vista.

Learning trends [edit]

In 1917, the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese was founded, and the academic study of Spanish literature was helped by negative attitudes towards High german due to World War I.[47]

Spanish is currently the almost widely taught language after English in American secondary schools and college education.[48] More than 790,000 university students were enrolled in Spanish courses in the fall of 2013, with Castilian the nigh widely taught foreign linguistic communication in American colleges and universities. Some fifty.6% of the over ane.5 million U.S. students enrolled in strange-language courses took Spanish, followed by French (12.vii%), American Sign Language (7%), High german (5.5%), Italian (4.6%), Japanese (4.3%), Chinese (3.9%), Standard arabic (2.one%), and Latin (one.7%). These totals remain relatively pocket-size in relation to the total U.S. population.[49]

Radio and media [edit]

Univisión is the country's largest Spanish linguistic communication network, followed past Telemundo. It is the country's quaternary-largest network overall.[fifty]

Castilian language radio is the largest non-English broadcasting media.[51] While strange language broadcasting declined steadily, Spanish broadcasting grew steadily from the 1920s to the 1970s.

The 1930s were nail years.[52] The early success depended on the concentrated geographical audience in Texas and the Southwest.[53] American stations were shut to Mexico, which enabled a steady circular flow of entertainers, executives and technicians and stimulated the creative initiatives of Hispanic radio executives, brokers, and advertisers. Ownership was increasingly concentrated in the 1960s and 1970s. The industry sponsored the at present-defunct merchandise publication Sponsor from the late 1940s to 1968.[54] Castilian-language radio has influenced American and Latino discourse on cardinal current affairs problems such every bit citizenship and clearing.[55]

Variation [edit]

There is a great diverseness of accents of Spanish in the United States.[56] The influence of English language on American Spanish is very important. In many Latino[57] (also called Hispanic) youth subcultures, it is mutual to mix Castilian and English to produce Spanglish, a term for code-switching between English and Spanish, or for Spanish with heavy English influence.

The Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española (North American Academy of the Spanish Language) tracks the developments of the Castilian spoken in the Us[58] and the influences of English.[59] [60]

Varieties [edit]

Linguists distinguish the following varieties of the Spanish spoken in the The states:

- Mexican Castilian: the US–United mexican states border, throughout the Southwest from California to Texas, also as in Chicago, but becoming ubiquitous throughout the Continental United States. Standard Mexican Spanish is often used and taught equally the standard dialect of Spanish in the Continental U.s..[61] [62]

- Caribbean Spanish: Spanish as spoken by Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans. It is largely heard throughout the Northeast and Florida, especially New York City and Miami, and in other cities in the East.

- Central American Spanish: Spanish as spoken by Hispanics with origins in Central American countries such every bit El Salvador, Republic of guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. Information technology is largely heard in major cities throughout California and Texas, also equally Washington, DC; New York; and Miami.

- Southward American Spanish: Spanish as spoken past Hispanics with origins in Due south American countries such as Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, and Bolivia. Information technology is largely heard in major cities throughout New York State, California, Texas, and Florida.

- Colonial Spanish: Castilian as spoken by descendants of Castilian colonists and early on Mexicans before the United States expanded and annexed the Southwest and other areas.

- Californian (1769–present): California, particularly the Central Coast

- Isleño Spanish (1783–present): St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana

- Sabine River Spanish: Parts of Sabine and Natchitoches Parishes, Louisiana, and the Moral community due west of Nacogdoches. Moribund, originated from rural Mexican Spanish.

- New Mexican Castilian: Central and north-primal New United mexican states and s-central Colorado and the edge regions of Arizona, Texas, and New Mexico, and southeastern Colorado

Many Spanish speakers in the US speak it equally a heritage language. Many of these heritage speakers are semi-speakers, or transitional bilinguals, which means they spoke Spanish in early on babyhood but largely switched to an English-speaking environment. They typically take a strong passive control of the linguistic communication, but never fully acquired it. Other, fluent heritage speakers have non undergone such a total shift from Spanish to English in their immediate family.

Transitional bilinguals often produce errors which are rarely found among native Spanish speakers just which are common among second-language learners. Transitional bilinguals ofttimes face difficulties in Castilian classrooms since teaching materials designed for English monolinguals and those designed for fluent heritage speakers are both inadequate.[63] [64]

Heritage speakers in full general accept a native or near-native phonology.[65] [66] [67]

Dialect contact [edit]

Spanish in the US shows mixing and dialect leveling between dissimilar varieties of Spanish in large cities with Hispanics of different origins.[68] [69] For example, Salvadorans in Houston show a shift towards lowered rates of /due south/ reduction,[70] due to contact with the larger number of Mexican speakers and the depression prestige of Salvadoran Castilian.

Los Angeles has its own vernacular Spanish variety, the result of dialect leveling between speakers of different, mainly central Mexican varieties. The children of Salvadoran parents who abound up in Los Angeles typically grow upward speaking this diversity.[62] Other cities may have their own vernacular Spanish varieties besides.[71]

Mutual English words derived from Castilian [edit]

Many standard American English language words are of Castilian etymology, or originate from 3rd languages merely entered English via Spanish.

- Admiral

- Avocado ( aguacate from Nahuatl aguacatl )

- Aficionado

- Banana (originally from Wolof)

- Buckaroo ( vaquero )

- Deli ( cafetería )

- Chili (from Nahuatl chīlli )

- Chocolate (from Nahuatl xocolatl )

- Cigar ( cigarro )

- Corral

- Coyote (from Nahuatl coyotl )

- Desperado ( desesperado )

- Guerrilla

- Guitar ( guitarra )

- Hurricane ( huracán from the Taíno storm god Juracán)

- Junta

- Lasso ( lazo )

- Patio

- Murphy ( patata ; come across Etymology of "potato")

- Ranch ( rancho )

- Rodeo

- Siesta

- Tomato plant ( tomate from Nahuatl tomatl )

- Tornado

- Vanilla ( vainilla )

Phonology [edit]

Spanish in the U.s. oftentimes has some phonological influence from English. For example, bilinguals who grew up in the Mesilla Valley in southern New Mexico nigh often pronounce ⟨r⟩ as a tap [ɾ] instead of a trilled [r] when information technology comes at the beginning of a discussion or subsequently a consonant. Even in discussion-medial position ⟨rr⟩ is ofttimes pronounced every bit a tap. The utilize of a trill is even less frequent in northern New United mexican states, where contact with monolingual Mexican Spanish is lesser.[72]

[five] has been reported as an allophone of /b/ in Chicano Castilian in the Southwest, both when spelled ⟨b⟩ and when spelled ⟨5⟩. This is primarily due to English influence.[73] [74] [75] Although Mexican Castilian more often than not pronounces /x/ as a velar fricative, Chicano Spanish often realizes it as a glottal [h], like English language'due south h audio. In addition, /d/ may occasionally be realized as a fricative in initial position.[74]

Much of the variation in U.s. Spanish pronunciation reflects the differences between other Spanish dialects and varieties:

- Like in most of Hispanic America, ⟨z⟩ and ⟨c⟩ (before /e/ and /i/) are pronounced equally [s], but like ⟨s⟩. Still, seseo (not distinguishing /s/ from /θ/) is also typical of the spoken language of Hispanic Americans of Andalusian and Canarian descent. Also, the English pronunciation of soft c helps to entrench seseo even though /θ/ occurs in English.

- Spanish in Espana, especially the regions with a distinctive /θ/ phoneme, pronounces /s/ with the tip of tongue against the alveolar ridge. Phonetically, that is an "apico-alveolar" "grave" sibilant [s̺], with a weak "hushing" audio that is reminiscent of retroflex fricatives. In the Americas and in Andalusia and the Canary Islands, both in Espana, Standard European Castilian /southward/ may sound similar to [ʃ] similar English sh as in she. However, that apico-alveolar realization of /s/ is mutual in some Latin American Castilian dialects which lack [θ]. Some inland Colombian Spanish, particularly Antioquia, and Andean regions of Republic of peru and Bolivia also have an apico-alveolar /southward/.

- American Castilian usually features yeísmo, with no distinction betwixt ⟨ll⟩ and ⟨y⟩, and both are pronounced [ʝ]. However, yeísmo is an expanding and now a dominant feature of European Castilian, peculiarly in urban voice communication (Madrid, Toledo) and peculiarly in Andalusia and the Canary Islands, but [ʎ] has been preserved in some rural areas of northern Kingdom of spain. Speakers of Rioplatense Spanish pronounce both ⟨ll⟩ and ⟨y⟩ as [ʒ] or [ʃ]. The traditional pronunciation of the digraph ⟨ll⟩, [ʎ], is preserved in some dialects along the Andes range, especially in inland Peru and the highlands of Colombia highlands, northern Argentine republic, and all of Bolivia and Paraguay.

- Most speakers with ancestors born in the littoral regions may debuccalize or aspirate syllable-terminal /s/ to [h] or entirely drop; this, está [esˈta] ("s/he is") sounds like [ehˈta] or [eˈta], as in southern Spain (Andalusia, Murcia, Castile–La Mancha (except the northeastern part), Canary Islands, Ceuta, and Melilla).

- ⟨g⟩ (before /e/ or /i/) and ⟨j⟩ are usually aspirated to [h] in Caribbean area and other littoral dialects besides equally in Colombia, southern United mexican states, and near of southern Spain. While it may exist [x] in other dialects of the Americas and often [χ] in Peru, that is a common feature of Castilian Spanish. It is normally aspirated to [h], like in most of southwestern Spain. Very often, peculiarly in Argentina and Republic of chile, [10] becomes more than fronted [ç] before high vowels /e, i/ and then approaches [ten] the realization of German ⟨ch⟩ in ich. In other phonological environments, information technology is realized as either [x] or [h].

- In many Caribbean dialects, the phonemes /l/ and /r/ tin be exchanged or sound akin at the end of a syllable: caldo > ca[r]do, cardo > ca[l]practise. At the end of words, /r/ becomes silent, which gives Caribbean Spanish a partial non-rhoticity. That occurs left often happens too in Ecuador and Chile[ citation needed ] and is a feature brought from Extremadura and westernmost Andalusia, in Spain.

- In many Andean regions, the alveolar trill of rata and carro is realized as an alveolar approximant [ɹ] or even a voiced apico-alveolar [z]. The alveolar approximant is specially associated with an indigenous substrate and is quite common in Andean regions, especially in inland Ecuador, Republic of peru, most of Bolivia, and parts of northern Argentina and Paraguay.

- In Puerto Rico, besides [ɾ], [r], and [50], syllable-concluding /r/ can be realized as [ɹ], an influence of American English: "verso"' (verse) tin can become [ˈbeɹso], also [ˈbeɾso], [ˈberso], or [ˈbelso]; "invierno" (wintertime) can become [imˈbjeɹno], aside from [imˈbjeɾno], [imˈbjerno], or [imˈbjelno]; and "escarlata" (scarlet) can become [ehkaɹˈlata], aside from [ehkaɾˈlata], [ehkarˈlata], or [ehkaˈlata]. Word-finally, /r/ is normally one of the post-obit:

- a trill, a tap, approximant, [fifty], or silent before a consonant or a intermission, as in amo [r ~ ɾ ~ ɹ ~ l] paterno 'paternal dearest', and amor [aˈmo],

- a tap, approximant, or [fifty] before a vowel-initial give-and-take, as in amo [ɾ ~ ɹ ~ 50] and eterno 'eternal love').

- Voiced consonants /b/, /d/, and /ɡ/ are pronounced as plosives after and sometimes before any consonant in most Colombian Castilian dialects (rather than the fricative or approximant characteristic of about other dialects), every bit in pardo [ˈpaɾdo], barba [ˈbaɾba], algo [ˈalɡo], peligro [peˈliɡɾo], desde [ˈdezde/ˈdeɦde], rather than [ˈpaɾðo], [ˈbaɾβa], [ˈalɣo], [peˈliɣɾo], [ˈdezðeastward/ˈdeɦðe]. A notable exception is the Nariño Section and most Costeño spoken communication (Atlantic coastal dialects), which feature the soft fricatives that are mutual to all other Hispanic American and European dialects.

- Discussion-finally, /n/ is oftentimes velar [ŋ] in Latin American Castilian and pan (breadstuff) is often pronounced ['paŋ]. To an English-speaker, the /n/ makes pan sound like pang. Velarization of word-final /n/ is so widespread in the Americas that only a few regions maintain the alveolar, /northward/, as in Europe: nigh of Mexico, Colombia (except for littoral dialects), and Argentina (except for some northern regions). Elsewhere, velarization is common although alveolar word-last /n/ appears amongst some educated speakers, especially in the media or in singing. Velar word-final /n/ is also frequent in Kingdom of spain, peculiarly in the Southward (Andalusia and the Canary Islands) and in the Northwest: Galicia, Asturias, and León.

Vocabulary and grammar [edit]

The vocabulary and grammer of US Spanish reflect English influence, accelerated modify, and the Latin American roots of almost U.s. Spanish. One instance of English influence is that the usage of Castilian words by American bilinguals shows a convergence of semantics between English and Spanish cognates. For case, the Spanish words atender ("to pay attention to") and éxito ("success") have caused a similar semantic range in American Spanish to the English language words "attend" and "exit." In some cases, loanwords from English turn existing Spanish words into homonyms: coche has come to acquire the additional meaning of "coach" in the United States, it retains its older meaning of "car."[76] Other phenomena include:

- Loan translations such every bit correr para 'to run for', aplicar para 'to apply for', and soñar de instead of soñar con 'to dream of' oftentimes occur.[77]

- Expressions with patrás , such as llamar patrás , are widespread. Though these appear to be calques, they likely represent a semantic extension.[77]

- Castilian speakers in the The states tend to use estar more often instead of ser . This is an extension of an ongoing trend within Spanish, since historically estar was used far less often.[78] For more information, see Spanish copulas.

- Spanish speakers in the southwest tend to employ the morphological future tense exclusively to express grammatical mood. The periphrastic construction ' ir + a + infinitive' is used for speaking nearly events that will occur in the future.[79]

- Disappearance of de (of) in certain expressions, equally is the case with Canarian Spanish: esposo Rosa for esposo de Rosa, gofio millo for gofio de millo, etc.[ citation needed ]

- Doublets of Arabic-Latin synonyms, with the Arabic form existence more common in American Spanish, which derives from Latin American Castilian and and so is influenced past Andalusian Castilian, like Andalusian and Latin American alcoba for standard peninsular habitación or dormitorio ('bedroom') or alhaja for standard joya ('jewel').[ citation needed ]

- See Listing of words having unlike meanings in Spain and Hispanic America.

Future [edit]

Castilian-speakers are the fastest growing linguistic group in the United States. Continued immigration and the prevalent Spanish-language mass media (such as Univisión, Telemundo, and Azteca América) back up Spanish-speakers. Moreover, the North American Free Merchandise Agreement makes many American manufacturers use multilingual production labeling in English, French, and Spanish, three of the four official languages of the Organization of American States (the other is Portuguese).

Likewise the businesses that always have catered to Hispanophone immigrants, a small simply increasing number of mainstream American retailers now advertise bilingually in Spanish-speaking areas and offer bilingual customer services. One mutual indicator of such businesses is Se Habla Español, which means "Spanish Is Spoken".

The annual State of the Union Address and other presidential speeches are translated into Castilian, following the precedent set by Bill Clinton's administration. Moreover, non-Hispanic American origin politicians fluent in Spanish speak in Castilian to Hispanic-majority constituencies. There are 500 Castilian newspapers, 152 magazines, and 205 publishers in the United States. Mag and local television advertising expenditures for the Hispanic market have increased substantially from 1999 to 2003, with growth of 58 per centum and 43 percent, respectively.

Historically, immigrants' languages tend to disappear or to be reduced by generational assimilation. Castilian disappeared in several countries and US territories during the 20th century, notably in the Philippines and in the Pacific Island countries of Guam, Micronesia, Palau, the Northern Marianas islands, and the Marshall Islands.

The English language-only move seeks to establish English every bit the sole official linguistic communication of the U.s.a.. Generally, they exert political public pressure upon Hispanophone immigrants to learn English and speak it publicly. As universities, business, and the professions use English, there is much social pressure to learn English for upward socio-economic mobility.

Generally, Hispanics (xiii.4% of the 2002 U.s. population) are bilingual to a caste. A Simmons Market place Research survey recorded that 19 percent of Hispanics speak only Spanish, 9 per centum speak simply English, 55 percent have express English proficiency, and 17 percent are fully English-Spanish bilingual.[80]

Intergenerational transmission of Castilian is a more accurate indicator of Spanish's futurity in the United States than raw statistical numbers of Hispanophone immigrants. Although Hispanics concur varying English proficiency levels, almost all second-generation Hispanics speak English, but virtually 50 percentage speak Spanish at home. Two thirds of third-generation Mexican Americans speak only English language at habitation. Calvin Veltman undertook in 1988, for the National Eye for Pedagogy Statistics and for the Hispanic Policy Development Project, the most consummate study of Anglicization by Hispanophone immigrants. Veltman's language shift studies document abandonment of Spanish at rates of 40 percent for immigrants who arrived in the US before the historic period of 14, and lxx percent for immigrants who arrived earlier the age of ten.[81] The consummate set up of the studies' demographic projections postulates the near-complete assimilation of a given Hispanophone immigrant cohort within two generations. Although his study based itself upon a large 1976 sample from the Bureau of the Census, which has not been repeated, information from the 1990 census tend to confirm the great Anglicization of the Hispanic population.

Literature [edit]

American literature in Castilian dates back to 1610 when a Spanish explorer Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá first published his epic poem History of New Mexico.[82] However, information technology was not until the late 20th century that Spanish, Spanglish, and bilingual verse, plays, novels, and essays were readily available on the marketplace through independent, merchandise, and commercial publishing houses and theaters. Cultural theorist Christopher González identifies Latina/o authors—such as Oscar "Zeta" Acosta, Gloria Anzaldúa, Piri Thomas, Gilbert Hernandez, Sandra Cisneros, and Junot Díaz—as having written innovative works that created new audiences for Hispanic Literature in the U.s..[83] [84]

Encounter also [edit]

- List of most commonly learned foreign languages in the United States

- List of U.South. cities with diacritics

- List of U.Southward. communities with Hispanic majority populations

- List of Spanish-language newspapers published in the Usa

- Biennial academic conference of Spanish in the United states

Full general:

- Bilingual pedagogy

- Spanglish

- Spanish linguistic communication in the Americas

- Spanish language in science and technology

- Listing of colloquial expressions in Honduras

- Spanish language in the Philippines

- History of the Spanish language

- Languages in the U.s.

References [edit]

- ^ a b c "Explore Demography Data".

- ^ "ISO 639-2 Language Code search". Library of Congress . Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ "Usa has more than Castilian speakers than Spain". theguardian.com . Retrieved 2016-05-09 .

- ^ Instituto Cervantes' Yearbook 2006–07. (PDF). Retrieved on 2011-12-31

- ^ "Más 'speak spanish' que en España". Retrieved 2007-10-06 . (Spanish)

- ^ How Many People Speak Castilian, And Where Is Information technology Spoken? Published past Babbel Retrieved 28 April 2018

- ^ "2000 Demography, Language in the US" (PDF) . Retrieved June five, 2007.

- ^ [1] Archived 2020-02-14 at annal.today American Community Survey, Language Spoken at Dwelling house by Ability to Speak English for the Population five Years and Over(Table B16001) 2013–2017 5-year estimates]

- ^ "Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española". Retrieved July thirteen, 2018.

- ^ "Castilian speaking declines for Hispanics in U.S. Metro areas".

- ^ a b Fuller, Janet M.; Leeman, Jennifer (2020). Speaking Spanish in the US : the sociopolitics of language (2nd ed.). Bristol, UK. ISBN978-1-78892-831-1. OCLC 1139025339.

- ^ David J. Weber, Spanish Borderland in N America (Yale UP, 1992) ch 1-5.

- ^ Santana Pérez; Juan Manuel (1992). Emigración por reclutamientos: canarios en Luisiana. Sánchez Suárez, José Antonio. Las Palmas de K.C.: Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Servicio de Publicaciones. p. 103. ISBN84-88412-62-2. OCLC 30624482.

- ^ a b c d Garcia, Ofelia (2015). "Racializing the Language Practices of U.Due south. Latinos: Impact on Their Education". In Cobas, Jose; Duany, Jorge; Feagin, Joe (eds.). How the Usa Racializes Latinos. Routledge. pp. 102–105.

- ^ Lipski 2008, pp. 214–216.

- ^ Abernathy (1976), p. 25, cited in Lipski (1987), p. 119

- ^ Lipski (1987), p. 119.

- ^ Van Young, Eric (2001). The Other Rebellion: Pop Violence, Ideology, and the Mexican Struggle. Stanford University Press. p. 324. ISBN978-0-8047-4821-half-dozen.

- ^ Lozano, Rosina (2018). An American linguistic communication : the history of Spanish in the Us. Oakland, California. ISBN978-0-520-29706-7. OCLC 1005690403.

- ^ a b Guadalupe Valdés et al., Developing Minority Language Resource: The Example of Spanish in California (Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 2006), 28–29.

- ^ Martin, Daniel Due west. (2006). Henke's California Law Guide (8th ed.). Newark: Matthew Bender & Co. pp. 45–46. ISBN08205-7595-X.

- ^ Winchester, J. (1850). The Statutes of California Passed At The First Session of the Legislature. San Jose: California Land Printer. p. 51.

- ^ McMurray, Orrin K. (July 1915). "The Ancestry of the Customs Holding Organization in California and the Adoption of the Common Police force" (PDF). California Law Review. iii (v): 359–380. doi:x.2307/3474579. JSTOR 3474579. Retrieved ix September 2020.

- ^ a b Crawford, James (1997). "Puerto Rico and Official English". Linguistic communication Policy.

- ^ Lipski 2008, p. 169.

- ^ Lipski 2008, p. 171.

- ^ a b Drew Walker (2010). "A Countries and Their Cultures: Venezuelan American". Countries and their cultures. Retrieved Dec ten, 2011.

- ^ Man, Anthony. "Afterward making South Florida dwelling, Venezuelans turning to politics". Sunday Sentry . Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ del Valle, Jose (2006). "The states Latinos, la hispanofonia, and the Language Ideologies of High Moderinty". In Mar-Molinero, Clare; Stewart, Miranda (eds.). Globalization and Linguistic communication in the Spanish-Speaking World: Macro and Micro Perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 33–34.

- ^ "What is the future of Spanish in the United States?". Pew Inquiry Center. five September 2013. Retrieved five March 2015.

- ^ Language Use and English-Speaking Ability: 2000. Census.gov.

- ^ "The Futurity of Spanish in the The states". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ Data Access and Broadcasting Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder – Results". Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "Primary language spoken at home by people aged 5 or older". United States Demography Bureau. 2010. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12.

- ^ Nasser, Haya El (Jan 2, 2015). "Candidates Facing More Latino Voters Who Don't Speak Spanish". Al Jazeera.

- ^ Furman, Nelly (December 2010). "Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United states of america Institutions of College Education, Fall 2009" (PDF). The Modernistic Language Association of America. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-12-13. Retrieved 2020-04-22 .

- ^ Bills, Garland D.; Vigil, Neddy A. (16 December 2008). The Spanish Language of New Mexico and Southern Colorado : A Linguistic Atlas. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN9780826345516.

- ^ a b Cobos 2003

- ^ Cobos 2003, pp. x–xi.

- ^ "Sec. 2054.001." Texas Legislature. Retrieved on June 27, 2010.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Robert (1985). "Acculturation or absorption: Mexican immigrants in Kansas, 1900 to World State of war II". The Western Historical Quarterly. 16 (4): 429–448. doi:ten.2307/968607. JSTOR 968607.

- ^ "U.S. Demography Agency QuickFacts: Liberal, KS". U.S. Census Agency. 2017.

- ^ "U.Due south. Census Agency QuickFacts: Dodge Metropolis, KS". U.S. Census Agency. 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Garden City, KS". U.S. Census Bureau. 2018.

- ^ Alanis, Kaitlyn (June thirteen, 2018). "Equally the Latino population grows in this rural expanse, youths are developing a new accent". The Wichita Eagle.

- ^ "Hispanic Media Sources in Kansas". USDA National Resource Conservation Service.

- ^ [ii], Leeman, Jennifer (2007) "The Value of Spanish: Shifting Ideologies in United states Language Teaching." ADFL Bulletin 38 (1–ii): 32–39.

- ^ Richard I. Brod "Strange Language Enrollments in The states Institutions of Higher Education—Fall 1986". Archived from the original on Nov 25, 2001. Retrieved September one, 2016. . AFL Bulletin. Vol. 19, no. ii (January 1988): 39–44

- ^ Goldberg, David; Looney, Dennis; Lusin, Natalia (Feb 2015). "Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Autumn 2013" (PDF). Mod Language Clan. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ D.M. Levine (2012-01-19). "Every bit Hispanic Television Market Grows, Univision Reshuffles Executives". Adweek . Retrieved 2013-10-02 .

- ^ Todd Chambers, "The state of Spanish-language radio." Journal of Radio Studies 13.1 (2006): 34–50.

- ^ Jorge Reina Schement, "The Origins of Spanish-Linguistic communication Radio: The Case of San Antonio, Texas," Journalism History 4:ii (1977): 56–61.

- ^ Félix F. Gutiérrez and Jorge Reina Schement, Spanish-Linguistic communication Radio in the Southwestern United states (Austin: UT Center for Mexican American Studies, 1979).

- ^ Andrew Paxman, "The Ascension of The states Spanish-Language Radio From 'Dead Airtime' to Consolidated Ownership (1920s–1970s)." Journalism History 44.three (2018).

- ^ Dolores Inés Casillas, Sounds of belonging: US Spanish-language radio and public advancement (NYU Press, 2014).

- ^ "Castilian Accents Spoken in the United States". BBC. November 25, 2019. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Hashemite kingdom of jordan, Miriam (April iv, 2012). "'Hispanics' Like Clout, Not the Label". The Wall Street Periodical.

- ^ "Misión". Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española . Retrieved March 23, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ ""Amenaza para la seguridad"". Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española . Retrieved March 23, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ ""Esto es": copia hispana de la redacción anglo". Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española . Retrieved March 23, 2001.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Villarreal, Belén (2013). "Why Los Angeles Spanish Matters". Voices. i (1).

- ^ a b Villarreal, Belén (2014). Dialect Contact amidst Spanish-Speaking Children in Los Angeles (PhD). UCLA. Retrieved 2021-05-29 .

- ^ Lipski 2008, pp. 56–64.

- ^ Lipski, John One thousand. (1999) [1993]. "Creoloid phenomena in the Spanish of transitional bilinguals" (PDF). Spanish in the U.s.a.. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 155–182. doi:x.1515/9783110804973.155. ISBN9783110165722.

- ^ Benmamoun, Elabbas; Montrul, Silvina; Polinsky, Maria, (2010) White Newspaper: Prologmena to Heritage Linguistics Harvard University

- ^ Chang, C. B, Yao, Y., Haynes, Eastward. F, & Rhodes, R. (2009). Production of Phonetic and Phonological Dissimilarity by Heritage Speakers of Mandarin. UC Berkeley PhonLab Almanac Report, 5. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5p6693q0

- ^ Oh, Janet Due south; Jun, Sunday-Ah; Knightly, Leah One thousand; Au, Terry Kit-fong (2003-01-01). "Belongings on to childhood language memory". Cognition. 86 (three): B53–B64. doi:ten.1016/S0010-0277(02)00175-0. ISSN 0010-0277. PMID 12485742. S2CID 30605179.

- ^ Lipski, John Yard. (2016). "Dialectos del Español de América: Los Estados Unidos" (PDF). In Gutiérrez-Rexach, Javier (ed.). Enciclopedia de Lingüística Hispánica (in Spanish). Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. pp. 363–374. doi:10.4324/9781315713441. ISBN978-1138941380.

- ^ Potowski, Kim. "El futuro de la lengua española en Estados Unidos". Youtube. Archived from the original on 2021-11-thirteen. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Aaron, Jessi Elana; Esteban Hernández, José (2007), "18. Quantitative show for contact-induced accommodation", Spanish in Contact, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 327–341, doi:10.1075/affect.22.23aar, ISBN978-90-272-1861-2 , retrieved 2021-03-nineteen

- ^ Melgarejo & Bucholtz (2020) mentions "Miami Spanish"

- ^ Waltermire & Valtierrez (2017), citing Vigil (2008) for the low frequency of the trill in northern New Mexico

- ^ Torres Cacoullos, Rena; Ferreira, Fernanda (2000). "Lexical frequency and voiced labiodental-bilabial variation in New Mexican Spanish" (PDF). Southwest Periodical of Linguistics. nineteen (ii): 1–17. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ a b Timm, Leonora A. (1976). "Three consonants in Chicano Castilian: /ten/, /b/ and /d/". Bilingual Review / La Revista Bilingüe. 3 (2): 153–162. JSTOR 25743678.

- ^ Phillips, Robert (1982) [1974]. "Influences of English on /b/ in Los Angeles Spanish". In Amastae, Jon; Elías-Olivares, Lucia (eds.). Spanish in the Usa: Sociolinguistic Aspects. New York: Cambridge University Printing. pp. 71–81. ISBN9780521286893.

- ^ Smead, Robert; Clegg, J Halvor. "English Calques in Chicano Spanish". In Roca, Ana; Jensen, John (eds.). Spanish in Contact: Issues in Bilingualism. p. 127.

- ^ a b Lipski 2008, pp. 226–229.

- ^ Silva-Corvalan, Carmen (September 1986). "Bilingualism and Linguistic communication Change: The Extension of Estar in Los Angeles Spanish". Language. 62 (3): 587–608. doi:10.2307/415479. JSTOR 415479.

- ^ Gutiérrez, Manuel J. (1997). "On the Futurity of the Hereafter Tense in the Spanish of the Southwest". In Silva-Corvalán, Carmen (ed.). Spanish in iv continents: studies in linguistic communication contact and bilingualism. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. pp. 214–226. ISBN9780878406494.

- ^ Roque Mateos, Ricardo (2017). A Skilful Spanish Book. University Bookish Editions. p. 37.

- ^ Faries, David (2015). A Brief History of the Spanish Language. Academy of Chicago Printing. p. 198.

- ^ López, Miguel R. (2001). "Disputed History and Poetry: Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá's Historia de la Nueva México". Bilingual Review / La Revista Bilingüe. 26 (1): 43–55. ISSN 0094-5366. JSTOR 25745738.

- ^ González, Christopher (2017). Permissible narratives : the promise of Latino/a literature. Columbus. ISBN978-0-8142-7582-5. OCLC 1003108988.

- ^ Fagan, Allison (2019-09-twenty). "Latinx Theater in the Times of Neoliberalism past Patricia A. Ybarra, and: Permissible Narratives: The Promise of Latino/a Literature by Christopher González (review)". MELUS: Multi-Indigenous Literature of the U.Due south. 44 (3): 197–201. doi:x.1093/melus/mlz028. ISSN 1946-3170.

Further reading [edit]

- Abernathy, Francis (1976). "The Spanish on the Moral". The Bicentennial Commemorative History of Nacogdoches. Nacogdoches: Nacogdoches Jaycees. pp. 21–33.

- Cobos, Rubén (2003). A Dictionary of New Mexico & Southern Colorado Spanish (2d ed.). Museum of New Mexico Printing. ISBN0-89013-452-9.

- Escobar, Anna María (2015). El español de los Estados Unidos . Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN9781107451179.

- Fuller, Janet Yard.; Leeman, Jennifer (2020). Speaking Spanish in the U.s. : the sociopolitics of language (2nd ed.). Bristol, UK. ISBN9781788928298.

- Lipski, John Grand. (1987). "El dialecto español de Río Sabinas: vestigios del español mexicano en Luisiana y Texas". Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica (in Castilian). 35 (1): 111–128. doi:x.24201/nrfh.v35i1.624. JSTOR 40298730.

- Lipski, John Chiliad. (2008). Varieties of Castilian in the United States . Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN9781589012134.

- Lozano, Rosina (2018). An American language : the history of Spanish in the United States . Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN9780520297074.

- Melgarejo, Victoria; Bucholtz, Mary (2020). "Oh, I don't even know how to say this in Spanish" (PDF). Spanish in Context. 17 (three): 488–510. doi:10.1075/sic.18028.buc. ISSN 1571-0718. S2CID 225015729.

- Vigil, Donny (2008). The traditional Castilian of Taos, New Mexico: Acoustic, phonetic and phonological analyses (PhD). Purdue University.

- Waltermire, Marking; Valtierrez, Mayra (2017). "The trill isn't gone: Rhotic variation in southern New Mexican Castilian". Journal of the Linguistic Association of the Southwest. 32 (two): 133-161.

Speaking Spanish in the Family United States Mixed Family

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_language_in_the_United_States

0 Response to "Speaking Spanish in the Family United States Mixed Family"

Post a Comment